Over the wall

From Christoph’s column in the New York Times, published in 2009.

Also included in the book “Abstract City”, published by Abrams.

On the evening of November 9, 1989, I was watching TV. The Berlin Wall was coming down, and I was flabbergasted.

From my eighteen-year-old perspective, the wall had always been there, and I had no reason to doubt that it would remain there forever. The news of the wall coming down was like somebody telling me that the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates had reversed course overnight, and that from now on you could stroll from Hamburg to Boston.

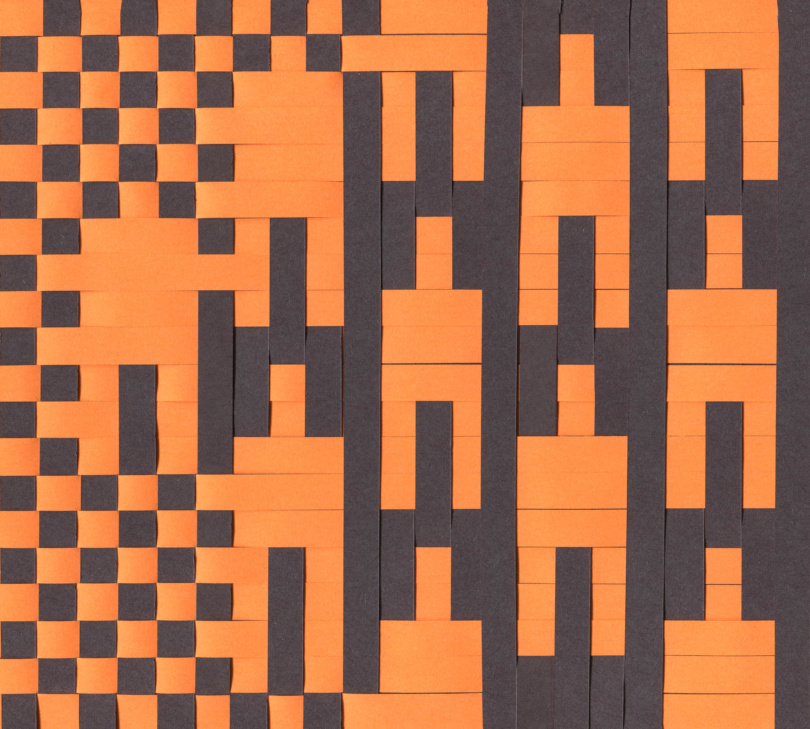

I saw pictures of people dancing on the wall in front of the Brandenburg Gate. Millions were out in the streets of Berlin, complete strangers were falling into one another’s arms, smiling and weeping at the same time. The images could not have been more emotional, but since I lived in southwestern Germany and we had neither friends nor close relatives on the other side of the wall in East Germany, it remained an abstract event.

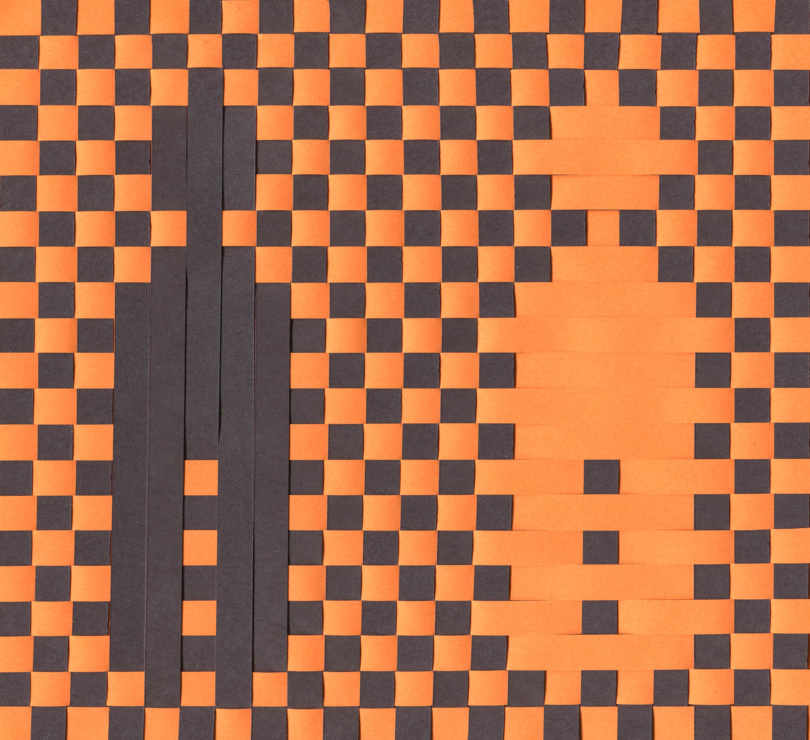

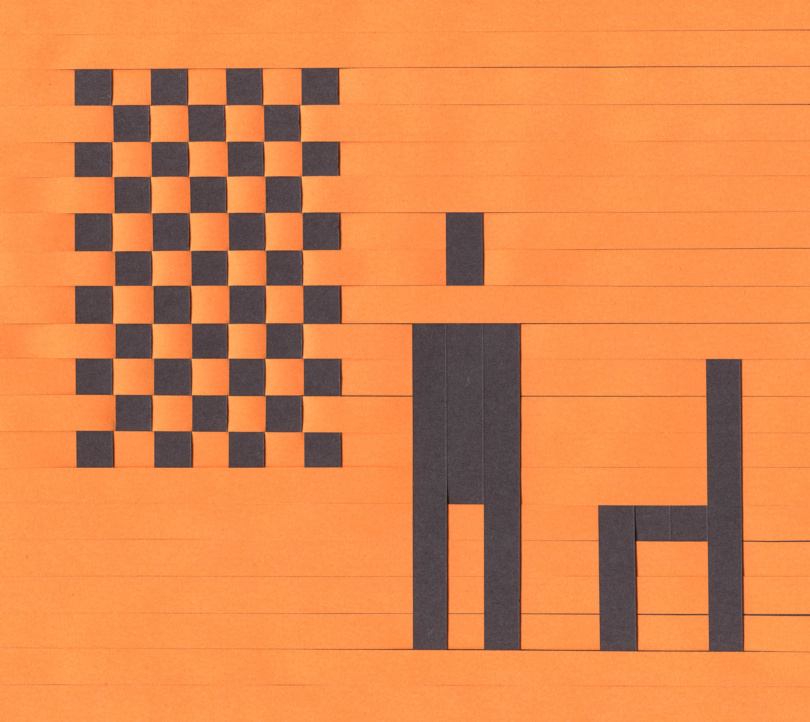

During my only visit to the divided Berlin, in 1988, I had experienced the city in all its terrifying absurdity. I vividly recall the so-called ghost stations of the subway:

Some Western subway lines passed through Eastern territory, resulting in a surreal commute. Imagine getting on the uptown 6 train at Union Square, but instead of stopping at Twenty-third, Twenty-eighth, and Thirty-third Streets, the train just slows down, and you are peeking out at dimly lit platforms patrolled by heavily armed soldiers from an enemy army. Then you get off at Grand Central to buy the paper and a bagel as if nothing had happened.

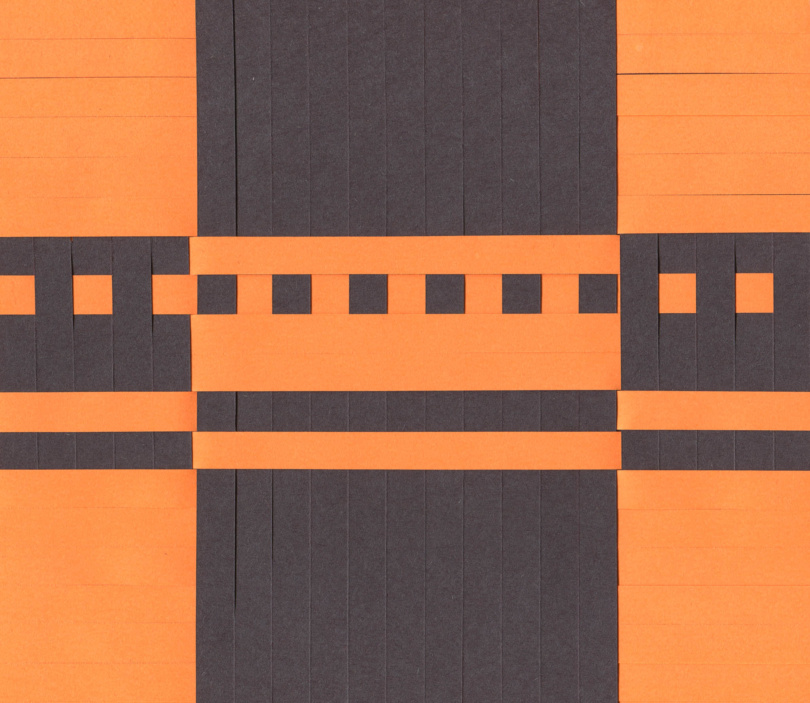

Officially, the wall existed to protect the citizens of the East from the capitalist aggressions of West Berlin. The day after the wall went up in 1961 the East German propaganda newspaper Neues Deutschland was filled with reports of thankful East Berliners. An article compared the orderly conduct of the socialist citizens with their counterparts in the West: “There was blood and thunder at the concert of American chief decadence apostle Bill Haley at the West Berlin Sports Palace. With our protective measures for the national border, however, everything passed off peacefully.”

The real reason the wall was built was different: East Germany was simply running out of citizens. Millions had fled by crossing the open inner city border of Berlin since the end of the war.

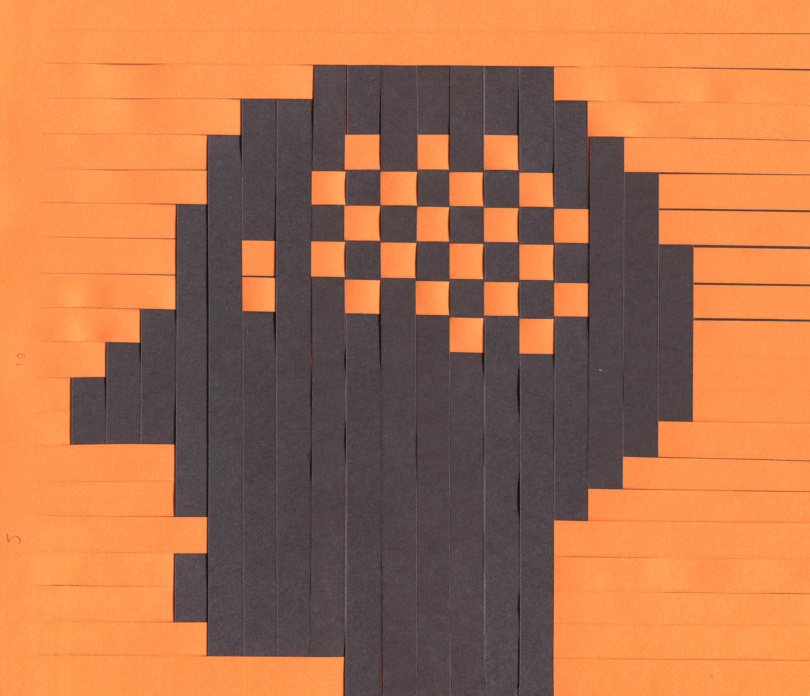

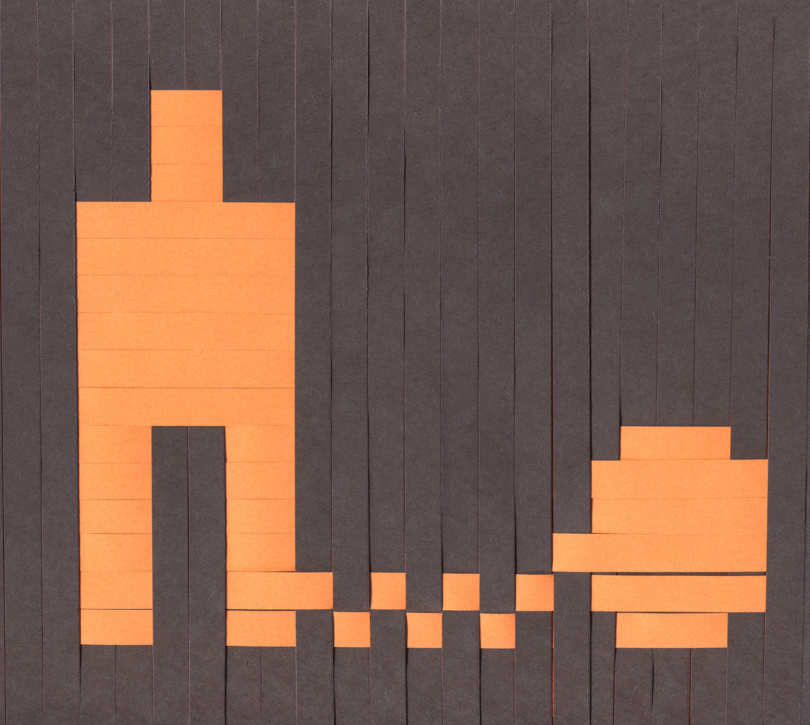

Today my family and I live just a few hundred feet away from Bernauer Strasse, where the wall ripped most callously through the city. In the early morning of August 13, 1961, East German police brigades started to seal off the border between the Soviet and the Allied sectors, splitting the city into East and West Berlin. In other neighborhoods, the divide often ran along a natural border, or at least through open spaces. Here it followed a regular residential street. People who lived on the south side of Bernauer Strasse woke up on the very frontier—their apartments were in the East, but the sidewalk in front of their building belonged to the West.

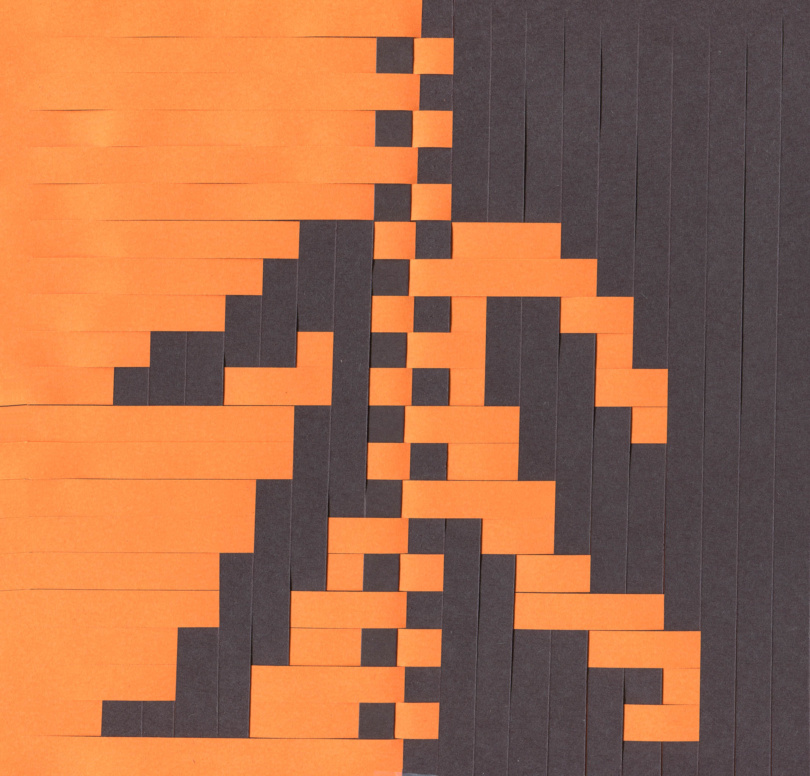

We moved from New York to Berlin last summer. Renovations at our home weren’t finished yet. We were exhausted. On top of that, we had a cranky baby who was content only when I put him in the stroller and took him for long walks exploring our new neighbourhood. Often we came by the Berlin Wall Memorial on the corner of Bernauer and Ackerstrasse. That’s when I first saw the old photos of people jumping out of their apartment windows to escape to the West. After the lower windows had been bricked up by the police, people tried to escape from the upper floors. They left behind forever their possessions, their friends, and often their families. Ida Siekmann died right here on August 22, 1961, the day before her fifty-ninth birthday, after jumping from her third-floor apartment. She was the wall’s first official victim.

And here I was, pitying myself because I had slept only a few hours and couldn’t get my DSL connection up and running.

In the first days after it went up, the wall was a barbed wire barrier. Conrad Schumann, a nineteen-year-old soldier in the East German army, was standing guard on the corner of Ruppiner Strasse and Bernauer Strasse. He was taunted and insulted by passersby from the West and, on a whim, started running and hurdled the barbed wire into the West, thus becoming the subject of one of the most dramatic photographs of the time. Only recently have I realized that I often go jogging up that very sidewalk.

Today our neighborhood is filled with bustling restaurants, shops, galleries, and playgrounds, which makes it all the more jarring to find out about all the drama

that unfolded here. A few feet away from where the boys and I play in a sandbox, my neighbors from forty-odd years ago had dug a tunnel through which fifty-seven people escaped before its existence was leaked to the secret police. Another photo at the memorial shows a bride and a groom waving at their parents from the other side of the barbed wire. They had probably lived just a few blocks from each other, and now found themselves in two separate, hostile nations. I think of our parents, who can just hop a train to come to Berlin to see their grandchildren perform a song in kindergarten.

While I try to get in touch with history through museums, books, and TV, twenty years ago history was actually being made, just a few blocks east in the church communities of the Prenzlauer Berg district. People risked losing their jobs, ruining their children’s prospects, and even being taken to one of the notorious Stasi prisons, yet they still worked in opposition groups for years. Like similar groups in Leipzig, they began organizing open demonstrations in the fall of 1989. Within weeks, these grew from a few dozen brave men and women to hundreds of thousands across the country, ultimately leading to the collapse of the socialist regime.

Germany, with a history so full of iron-fisted terror, war, and wanton violence, had finally experienced a revolution without a single bullet being fired.

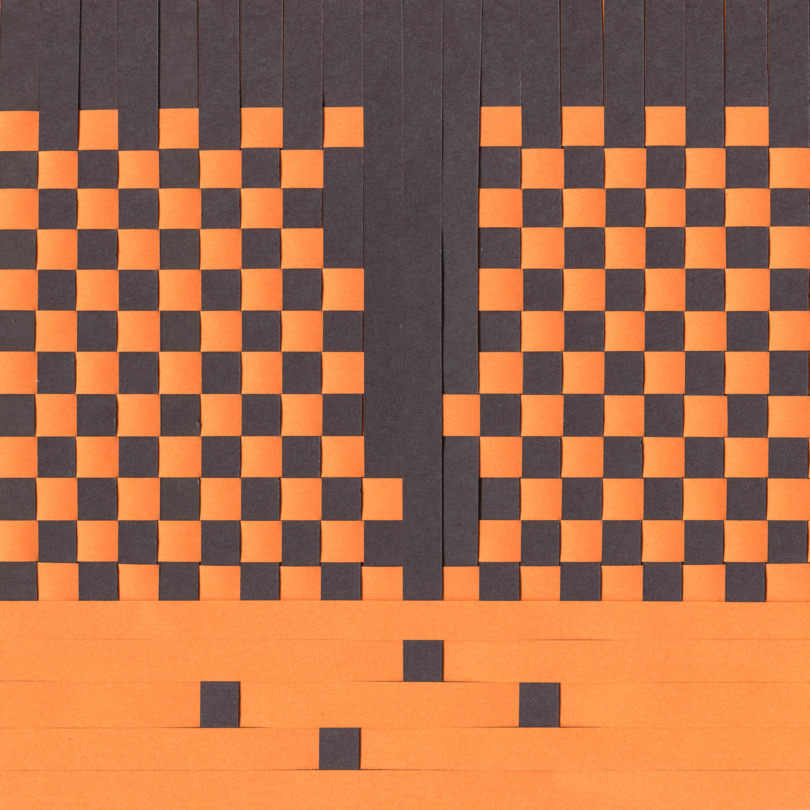

For twenty-eight years the wall in Berlin was one of the world’s most frightening and impermeable borders. Few made it to the other side; most who tried were captured and thrown into prison, and many were killed in the attempt. Today, there are only very few places where the wall still exists. Instead, a twin row of cobblestones is laid into the streets of Berlin, indicating where the wall once stood.

Every time I ride my bike across this artificial scar, I quickly close my eyes and appreciate the small, humbling bump.